Everyone wants access to clean drinking water that tastes good. Fortunately, many areas of the US have very safe drinking water, but some locations struggle with particular contaminants or flavor issues, and private wells need filtration regardless. Moreover, some cities have older infrastructure which can worsen water quality or safety. Having or installing a water filter in your home is a good way to solve these problems. The additional filtration may be especially helpful for anyone with a compromised immune system, such as those living with cancer or HIV/AIDS.

In this article, we’ll discuss what contaminants you should be on the lookout for and what types of water filters can get rid of them.

Know your contaminants before you buy

Water filtration systems catch and remove harmful contaminants from water, but some systems are better at filtering certain contaminants than others. There is no filter that will successfully remove all contaminants. For this reason, your first step should be to learn which contaminants you should target with a filter. Keep in mind that contaminants can be regional, local, or even home-based. Some are also slightly seasonal.

If you’re in the US and get your water from a municipal source, start by visiting the EPA’s website on the Safe Drinking Water Act. Under this act, local areas are required to produce an annual Consumer Confidence Report. This is a water quality report that goes into detail about which contaminants and concerns are affecting your community’s drinking water. You may receive one of these in the mail each year. If not, you can find or request one.

On private well water or otherwise not hooked into a community water source? You won’t receive a Consumer Confidence Report, but you can buy a water test kit to learn which contaminants your home in particular may be dealing with. Note that the best water test kits will make use of a certified lab.

The EPA recognizes four categories of water contaminants:

- Physical contaminants that affect water’s appearance (e.g., sand, leaves, other sediment)

- Chemical contaminants from natural or man-made sources that can harm flavor or safety (e.g., bleach; heavy metals, like lead or mercury; pesticides; drugs)

- Biological contaminants that affect water’s safety, such as bacteria, viruses, protozoa, and parasites

- Radiological contaminants that emit ionizing (cancer-causing) radiation (e.g., plutonium and uranium)

Micron ratings

You’ll often see filters rated according to microns: .1-micron, .5-micron, 5-micron, 10-micron, and so on. These ratings refer to the size of the material the filter is able to catch.

The larger/higher the micron rating, the more capable it is of catching large contaminants. The smaller/lower the rating, the more capable it is of catching fine contaminants. If a filter has a 10-micron rating, that means it only filters out larger materials. If it has a 1-micron rating or even lower, that means it catches very fine particulates.

It’s not right to think of high- or low-rated micron filters as being better or worse than each other. Some water sources deal with larger pollutants, while others deal with small ones.

These ratings are sometimes said to be nominal or absolute. When a micron rating is nominal, it means that it has a higher margin of error. It’s able to remove contaminants of that size most—but not all—of the time. When a micron rating is absolute, the manufacturer is claiming the filter is able to remove contaminants of that size almost always, usually 90% or more of the time.

Types of water filters

Once you know which contaminants you should be tackling, you can start deciding on water filters. And that’s key: focusing on the filter, not the filtration system. While some forms of filtration systems may better suit your home’s architectural or space needs, all filtration systems are using similar kinds of filters within them. It’s the filter—or, often, filters, plural—that determine improvements to taste and safety. This is the first thing you want to focus on.

PUR’s Ultimate water dispenser is an example of a water filtration system

Whatever filtration system you decide to use, make sure the manufacturer’s claims about the filters inside it are factual, if not backed by an independent authority. And remember that the more filter types there are in a filtration system, the more likely it is to catch a variety of contaminants.

Point-of-use vs. point-of-entry filtration systems

Most filtration systems available to the consumer are point-of-use systems, meaning they only target the water that is specifically introduced to them. Water filter pitchers and faucet-mounted filtration systems are two examples of point-of-use systems.

ZeroWater’s 10-cup water filter pitcher is an example of a point-of-use system. Inside, it uses a 5-stage filter, passing water through materials such as sand and carbon block.

The major advantage of point-of-use filtration is that it’s usually cheap, and so easily used and easily replaced. It’s also almost guaranteed to improve the taste of your water and will likely target other contaminants, too. For most American homes, point-of-use filtration systems are more than enough to improve taste and further guard against contaminants.

For more extensive protection, you’re going to want a point-of-entry system that filters all the water entering your home. Whole house filtration systems are ideal if you have well water or if you have contaminants that cause you woes outside of taste and health concerns (e.g., harmless metal levels that cause difficult-to-clean staining). The downside to point-of-entry systems is they can be expensive to install, maintain, and repair, but there are affordable ones out there.

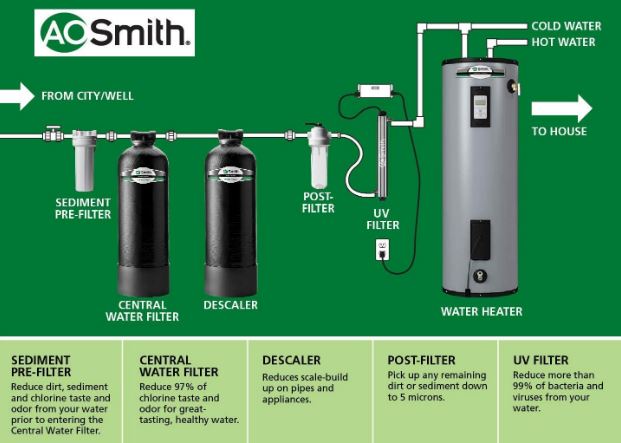

AO Smith’s whole house water filtration system, which uses sediment, carbon, and UV filters to improve taste, appearance, and safety for the entire home

Carbon filters

You’ll see carbon filters listed in a couple of ways, namely carbon block, coconut shell carbon, and activated carbon (or activated charcoal). These identifiers are misleading, as most all consumer-grade carbon filters on the market today make use of activated coconut shell carbon, which is far more effective and safer than older carbon filters that used wood- or coal-based activated carbon.

All carbon filters work similarly. As a porous material, carbon has holes through which water can pass. When “activated” (processed a certain way), these pores are especially tiny but still allow water to pass. But carbon’s surface is adsorbent, meaning it basically works like a sticky trap against many of the molecules it comes into contact with. Its surface is not too attracted to water’s chemical makeup (or, unfortunately, to most heavy metals), but it’s very attracted to numerous common pollutants.

Many times, it’s just a matter of how activated carbon is structured in the filter. Two of the most common carbon forms you’ll encounter are carbon block and granular activated carbon (GAC). Most carbon filters are in a block form.

This is what a carbon block filter looks like on the inside. See Express Water’s activated carbon block water filters

- Carbon block filters make use of a solid block of activated carbon. Because it’s solid, its pores are very tiny, meaning it’s better at trapping contaminants than some of the other carbon forms. Unfortunately, this solid form also makes it much slower for water to pass through.

- Granular activated carbon (GAC) filters have broken the carbon down into, as the name implies, granules. If you pick up a GAC filter and give it a good shake, you’ll hear the granules sifting inside like uncooked rice in a container. GAC filters have the advantage of being faster (because they’re more porous), but that also means they aren’t as effective at removing contaminants. If taste is your sole concern, they’re a great option.

This is what granular activated carbon looks like on the inside of filters. You can actually buy it in bulk

If you choose a carbon filter, look for information on the adsorption potential of that filter. The more adsorptive the filter, the more contaminants it will catch.

Outside of basic water filter pitchers and many faucet-mounted systems, you’ll find carbon filters are often paired with another filter that catches the types of contaminants carbon tends to miss.

Frequently found in: Water filter pitchers, countertop systems, faucet-mounted systems, under-sink systems, whole house systems

Good at filtering: Lead (sometimes), pesticides (sometimes), radon (when coupled with aeration), the taste of chlorine and other community disinfection byproducts

Bad at filtering: Heavy metals (usually), disease-causing microorganisms

Recommended for: Improving flavor, removing larger organic contaminants and non-metals

Price range: Replacement carbon filters range from the very cheap (under $20) to the very expensive ($400+). Expense is related to the type of filtration system used, with the most expensive carbon filters typically found in whole house or under-sink reverse osmosis systems.

Ion exchange filters

Ion exchange filter cartridges are filled with a beaded resin that has been chemically altered to interact with the water molecules that go through the beads. There are two main types of ion exchange filter commonly available for home use.

- The water softening (cation) type filters hard water, which contains calcium and magnesium, into a softer form, which then contains more sodium. These are common in water filter pitchers.

- The other ion exchange filter is often called an organic trap filter (anion) and removes discoloration and odors caused by tannins and nitrates. These are more common in whole house filters.

The other two kinds of ion exchange filters are much more common in industrial applications and the treatment of city water. They are more complicated and expensive to operate but filter out a wider range of contaminants. SAC resin (a stronger version of water softeners) removes a variety of heavy metal contaminants, as well as a number of common minerals. SBA resin (a stronger version of organic traps) removes chlorides, sulfides, and arsenic, as well as other organic compounds. Watch out for domestic ion exchange filters that claim to provide the benefits of the industrial kinds with the cost and ease-of-use of the domestic types.

If you’d like to understand more behind the science of these filters, check out this video.

Ion exchange filters are found in many different devices that need water to pass through them. See Breville’s resin ion exchange water filters, which are found in their coffee and espresso machines.

You’ll often see water softening ion exchange filters paired with activated carbon filters in simple filtration systems, like filter pitchers. They also sometimes appear in larger and more comprehensive systems as a type of descaling (water softening) pre-filter, which improves the service life of these larger, more expensive systems.

While these filters are good at removing a couple of contaminants, its strength is really in its ability to soften water and prevent buildup in devices. For this reason, you’ll sometimes even see them in coffee machines.

Frequently found in: Water filter pitchers, reverse osmosis systems, whole house systems

Good at filtering: Calcium, magnesium, and radium (for the water softening type), nitrates and tannins (for the organic trap type)

Bad at filtering: Bacteria and viruses; keep in mind that the two types of domestic ion exchange filters filter different things

Recommended for: Areas with hard water (water softeners), people with well water (organic traps)

Price range: Ion exchange filters appear in many filtration systems of varying cost. Replacement filters are generally cheap and run from $15-25 for most kinds.

Reverse osmosis filters

Globally, reverse osmosis is the most common water purification process in use today. You’ll sometimes see it referred to as “RO” for short. If you feel a little confused by what RO means or encompasses, don’t feel bad. The term is confusing because it can refer to a kind of water purification process (a system), as well as the semipermeable membrane (a filter) the process uses.

In units that make use of reverse osmosis, pressure is applied to the water in the unit, which pushes it toward a semipermeable membrane. This membrane catches a majority of contaminants, both large and extremely small. While very effective at water purification, RO is slow and produces wastewater—as much as three times more wastewater than clean water. This wastewater must be drained out elsewhere.

Reverse osmosis is really only found in under-sink filtration systems which tend to feature several kinds of filters as well as the semipermeable membrane filter.

Frequently found in: Under-sink systems

Good at filtering: Bacteria and viruses, lead, nitrates, dissolved solids, including minerals. RO will give you some of the best-tasting water that is also safe—so long as you like the taste of water that has no minerals.

Bad at filtering: Quickly! RO filtration systems are slow because the passage of water through the semipermeable membrane is slow. For this reason, RO systems have a tank that keeps some amount of purified water stored ahead of time for future use.

Recommended for: Those who want comprehensive filtration, don’t mind losing minerals in their water, and have a cheap water source. Because of how much wastewater RO systems produce, if water is expensive in your area, this will be an expensive filtering option.

Price range: While under-sink RO systems can be slightly expensive to buy and install (~$200 range), especially for those that have larger tanks, the replacement membrane filters tend to be well under $100 or even $50. For some, the real cost of RO systems over time will be the cost of the water itself due to the wastewater this process produces.

UV light filters

Despite being a newer filter on the block, UV light filtration has quickly caught on and accounts for a large portion of the water purification market, though often at more industrial levels. With this filtration, the water that enters the filter is “zapped” with a burst of UV light. This light damages or destroys the DNA structure of microorganisms.

UV filters are ideal for treating water that may become contaminated by bacteria and viruses, but it won’t clear out chlorine flavor, metals, or pesticides. For this reason, it’s often paired with another filter in most filtration systems.

Frequently found in: Under-sink systems, whole house systems

Good at filtering: Bacteria and viruses, including Cryptosporidium and Giardia

Bad at filtering: Metals, nitrates, pesticides, etc; anything that affects taste. Really only good at dealing with microorganisms.

Recommended for: People with compromised immune systems

Price range: The cheapest UV sterilizer systems start at $250 and work their way up to well over $1500, according to whether they contain other filtering methods. Replacing the UV bulbs can range in cost from $20 to well over $100.

Sand filters

Slow sand filters are a good option if you have private well water, instead of being connected to a municipal water system. In fact, this type of filtration is one municipal systems often use to purify water. Slow sand filters are adapted for the household, but if you’re looking to get the kind of water more connected households have access to, this is a good way to start if you own your home.

These filters work by way of layers of sand and gravel, as well as a protective bioactive layer. So long as the water doesn’t contain lots of debris, it will flow through a sand filter with relative ease. The “slow” in the slow sand filter terminology really only refers to how sand filters for the home are slower than industrial scale ones.

Most sand filters for the home are contained in standard-sized cartridge filters for whichever filtration system requires it. Here, though, you can see how they work on a larger scale in HydrAid’s BioSand water filter. Image from Wikimedia.

Sand filters are mostly affordable upfront, and cheap in the long run, as they tend to last with few maintenance requirements for up to 10 years. This is assuming they are the only filter style in use—an important fact, as many filters available to the consumer use multiple filter types in a single system, meaning this or other parts of the system may last longer than others.

Frequently found in: Whole house systems, under-sink systems, some countertop systems

Good at filtering: Nearly all protozoa, 90-99% of bacteria, some viruses

Bad at filtering: Man-made chemicals (including chlorine), heavy metals, many viruses

Recommended for: People who use a private water source. Great for pools.

Price range: Sand filters can be found in very expensive whole house systems (think $3500+), but they’re also sometimes found in more affordable under-sink reverse osmosis systems that cost under $300. On the very cheapest end (<$100), they sometimes appear in countertop systems.

Sediment filters

Unlike many filters, which are named for what they use to remove contaminants, sediment filters are actually named for what they remove from water: sediment. These filters remove sand and other solid materials that tend to sink in water and settle at the bottom of any container you might put it in.

Most frequently, you’ll find sediment filters are prefilters—that is, they are the first filter water encounters before it comes into contact with a second filter, such as a carbon filter or UV light filter. By first filtering out larger debris, more delicate filters are protected from them and will last much longer.

Frequently found in: Whole house systems

Good at filtering: Large debris, sand, and really anything solid, including some forms of iron, which can discolor water.

Bad at filtering: Liquid or microscopic contaminants, though the sediment filters with the smallest micron ratings may be able to catch some.

Recommended for: Anyone who needs a prefilter to protect other, more delicate filters. Good for well water to help remove large organic matter.

Price range: While the whole house systems they’re a part of are expensive, replacement sediment filter cartridges are cheap, with most typically well under $30.

Water filter starter kit

Overwhelmed by the information above? Here are the basics:

- Just looking to improve the flavor of your water? Look for a filtration system that has a carbon block filter, like Brita’s Stream Rapids water filter pitcher. If you only have a minor flavor complaint, a GAC filter, like the one found in Brita’s UltraMax, may be enough for you, as well, and it will filter water faster.

- If you’re looking to solve more than a simple flavor problem, find out what contaminants you’re dealing with. Access or request your Consumer Confidence Report if you’re on a community source of water or buy a water test kit. We recommend SimpleWater Labs’ Tap Score, which uses certified testing labs to analyze water samples.

- Know which contaminants you need to combat? Get a multi-stage filtration system. Whatever filters are right for your situation, a filtration system that makes use of multiple filters will offer you the best results.